Risk assessment modelling approaches and tools

“Chemicals in their nanoparticle form have properties that are completely different from their larger physical forms and may therefore interact differently with and in biological systems”. “As a result, it is necessary to assess the risks arising from any nanoparticle that will potentially come in contact with humans, other species or the environment, even if the toxicology of the chemicals that make up the nanoparticle is well known.” (Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR))

Table of contents

Nanotechnology is among the fastest growing technologies over the past few years, due to a wide range of applications of engineered NMs. However, the scientific community, the regulatory agencies and the industrial sector that designs and produces NMs are highly concerned about the potential adverse effects of NMs on human health and on the environment, which may be different to those arising from conventional chemicals or from micrometric particles (with bigger sizes). Due to their size in the nanoscale, NMs have a greater surface area, which enhances their chemical reactivity and may result in higher production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and eventually lead to toxicity. The size and shape of NMs also allows them to move through the body and reach various organs and tissues. The distinct features of NMs and their effect on safety have attracted the interest of many researchers and practitioners in the nanotechnology area and drove the development of various RA frameworks, specific to NMs. Oomen et al., 2018 published a comprehensive and detailed review, addressing the aim, regulatory readiness, advantages, and disadvantages of 14 different RA frameworks and their applicability for NMs. All frameworks assessed followed the risk assessment paradigm, consisting of hazard identification, exposure assessment and risk characterisation, but differed in their aims, applicability domains, basic assumptions and alignment to one or more regulations. It is stated in this review paper that due to NM complexity it is not possible to construct an adequate RA framework to suit all routes of exposure for mammalian and ecological receptors. In another review paper (Hristozov et al., 2016) the inclusion of in silico methods and approaches in RA frameworks is highlighted.

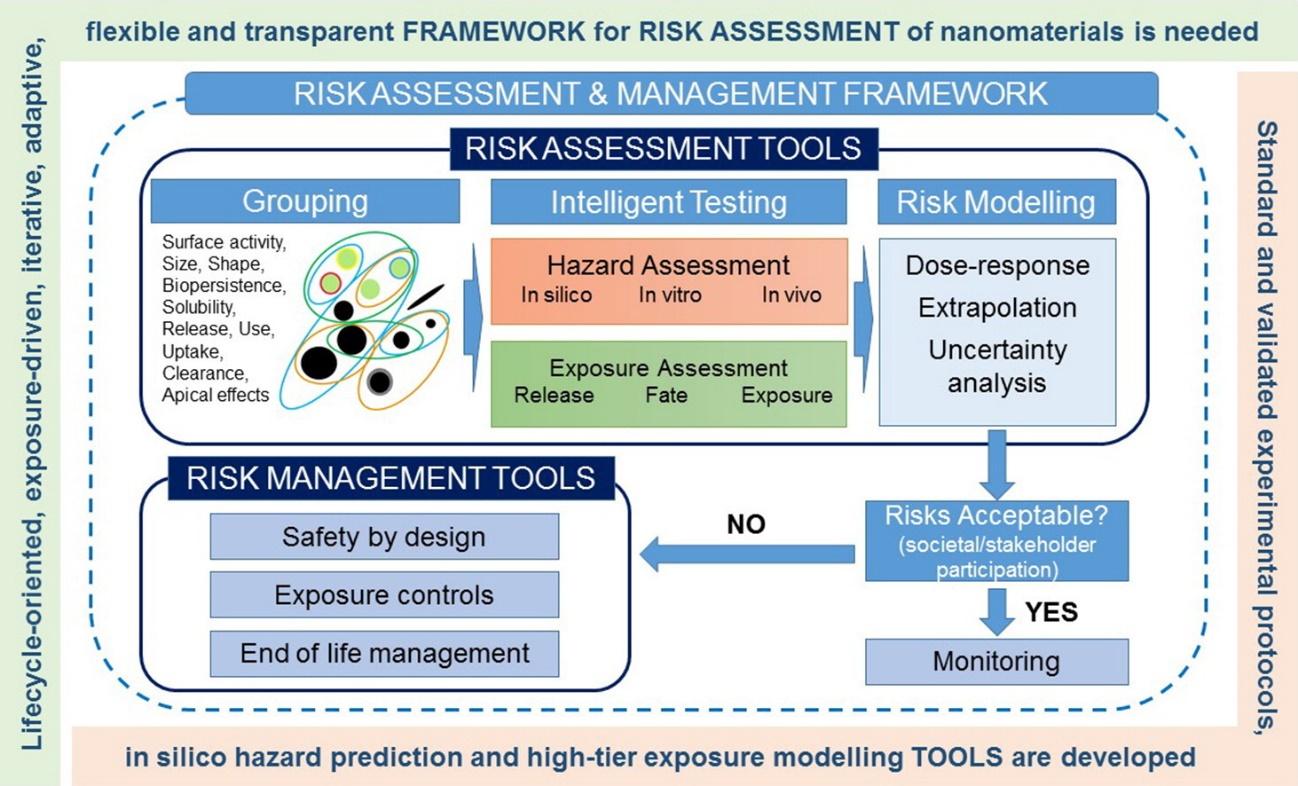

Figure 1. Frameworks and tools for risk assessment of manufactured nanomaterials (extracted from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.07.016)

Towards this direction, OECD has recently published a framework for Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA) (OECD, 2016), based on the concept of AOPs, which is based to a large extent on in silico modelling. The proposed framework is described in detail in NanoCommons D6.1 “A workflow and checklist for experimental design and informatics workflow for risk assessment” and combines nicely three different modelling methodologies to form a RA strategy. An exposure model predicts the external concentration, a toxicokinetics model determines the concentration of a substance in the various organs of the species of interest and the likelihood that a chemical reaches the target organs and a nanoQSAR or a grouping/read-across approach predicts if an AOP will be triggered.

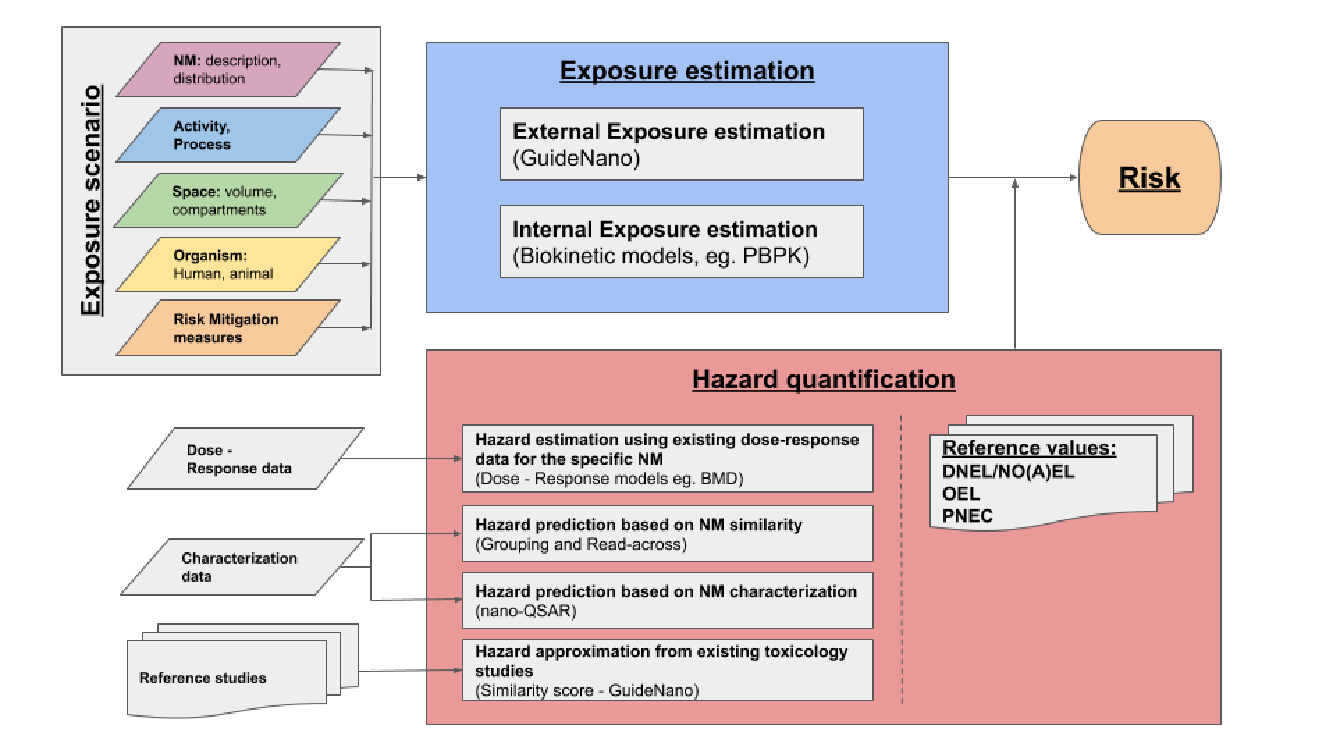

Figure 2. Overview of the NanoCommons nanoinformatics based RA framework. A key aspect of the workflow is integrating the different aspects, and automating the process to enable the RA to be run end-to-end.

Although the number of tools and models for NMs RA is growing, their use by industrial organisations and regulation agencies is not mainstream yet. Lack of sufficient data to support all steps required for RA is certainly one reason. We believe that one additional missing element is sufficiently described RA best practices and integrated user-friendly workflows that can guide users through the RA tools and provide navigational support on how to combine and link the different tools and approaches in order to arrive at reliable and well-validated RA and decisions. The NanoCommons project aims to develop pipelines and workflows that will fill this gap, and indeed to automate the whole process of RA, including provision of access to high quality data to run the models via the NanoCommons Knowledge Base.

A series of risk assessment methodologies, web services and tools have been developed. These tools can be divided into two categories; standalone risk assessment tools, which can be used to conduct risk assessment end-to-end, and risk assessment submodules, which generate missing information that can be integrated in an overall risk assessment framework. The latter can be further divided into two distinct groups: hazard quantification tools and exposure estimation tools.

Hazard Quantification

Hazard quantification is one of the two major risk assessment pillars, along with exposure estimation. The aim is to predict a toxicological threshold, commonly termed Point-Of-Departure (POD), that when crossed, causes significant biological perturbations that can lead to a downstream adverse outcome at the organism level. This can be realised either through drawing information directly from available literature, or through analysing in vivo or in vitro dose-response data using appropriate dose-response methodologies. In the absence of experimental toxicology data, in silico methodologies, e.g. read-across and nano-QSAR models, can be employed for hazard estimation using existing data.

Exposure Estimation

Exposure estimation is a pivotal module of every risk assessment workflow. An exposure model predicts the external concentration, which can then be used as input to a biokinetics model for determining the concentration of a substance in the various organs of the species of interest and the likelihood that a chemical reaches the target organs.

Physiologically-based kinetics modelling

Risk Characterization Ratio calculation

The core component of a RA workflow aims to compare the level of exposure with the relevant hazard limit value to calculate the respective Risk Characterization Ratio (RCR). The first step for creating an exposure scenario(s) is to gather the data regarding the ENM of interest. In particular, its physicochemical properties, and detailed information related to the process (during which exposure may occur), the duration of the exposure, the exposed organism(s) as well as ecological data -if available- are incorporated into each scenario. When both the exposure level and the relevant hazard reference point are available, the calculation of the RCR is direct. If this is not the case, many alternative modelling tools and approaches for estimating the exposure levels and predicting the hazard reference points (RPs) can be employed.

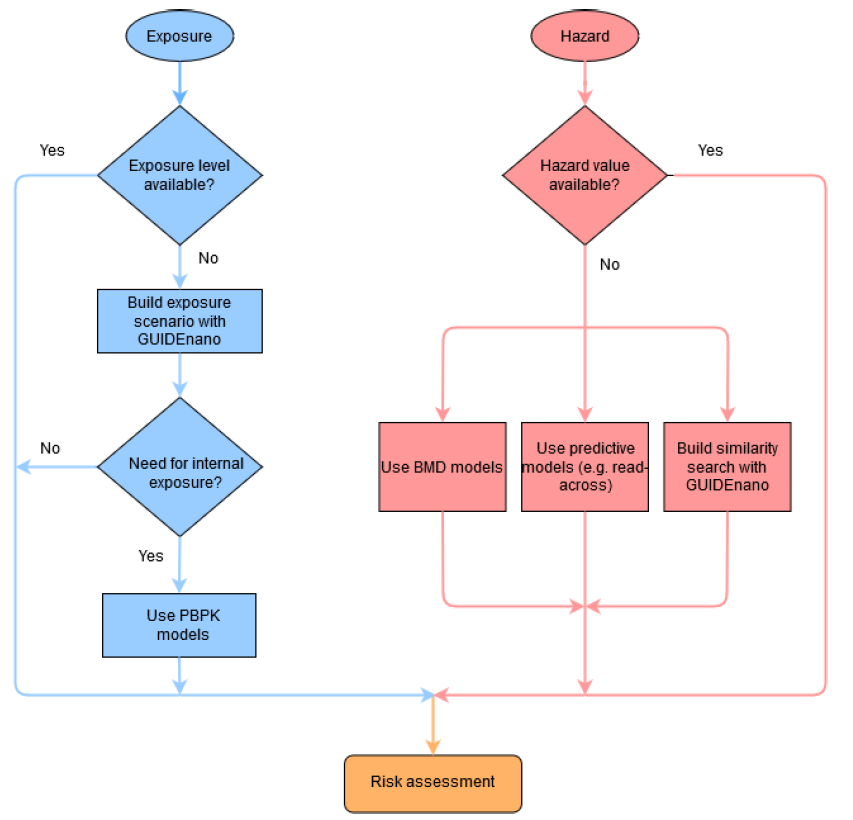

Figure 3. NanoCommons workflow for conducting risk assessment through the integration of exposure and hazard assessment modules

To demonstrate the workflow, a case study illustrates how the GUIDEnano exposure module, a PBPK model and a BMD analysis of transcriptomics data can be integrated in a complete RA framework. The web application estimates the risk of triggering AOP 173 (Lung Fibrosis) due to exposure to TiO2 engineered nanoparticles.

The case study can be accessed through: http://www.enaloscloud.novamechanics.com/nanocommons/exposure/

Risk Assessment Tools

References

- Hristozov et al., 2016: Hristozov, D.; Gottardo, S.; Semenzin, E.; Oomen, A.; Bos, P.; Peijnenburg, W.; van Tongeren, M.; Nowack, B.; Hunt, N.; Brunelli, A.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Tran, L.; Marcomini, A. Frameworks and tools for risk assessment of manufactured nanomaterials. Environ Int 2016 95, 36–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.07.016

- OECD, 2016: OECD Guidance Document for the Use of Adverse Outcome Pathways in Developing Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA). OECD Series on Testing Assessment No. 260 JT03407308, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1787/44bb06c1-en

- Oomen et al., 2018: Oomen, A.G.; Steinhäuser, K.G.; Bleeker, E.A.J.; van Broekhuizen, F.; Sips, A.; Dekkers, S.; Winjnhoven; S.W.P., Sayre, P.G. Risk assessment frameworks for nanomaterials: Scope, link to regulations, applicability, and outline for future directions in view of needed increase in efficiency. NanoImpact 2018, 9, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IMPACT.2017.09.001