Nano-QSAR developement and models

Computational models that predict adverse biological effects of engineered NMs (ENMs) are becoming increasingly important to support risk assessment.

This is primarily due to the cost-saving and reduction of attrition rates they help achieve, since market candidates under development can be assessed for toxicity early-on in the process. Therefore, candidates predicted to be toxic can be discarded before a significant amount of time and effort has been invested, and most significantly, before expensive experimental tests need to be carried out. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models are mathematical models derived from the algorithmic analysis of available experimental activity training data, which are able to predict the unknown activities of other compounds, directly from structural characteristics (called “descriptors”). In the nano-domain it is common to refer to QSARs that are applied to NMs as nano-QSARs.

Overall, nano-QSARs can be grouped into regression and classification models. Statistical and machine learning modelling techniques, such as multiple linear regression (MLR) (Gajewicz et al., 2015, Puzyn et al., 2011, Pan et al., 2016), logistic regression (Pandharipande et al., 2009), Naïve Bayes (Liu et al., 2013) , decision tree analysis (Hansen et al., 2013), random forest (Oh et al., 2016), k-nearest neighbour (Cassotti et al., 2014 and Fourches et al., 2010), partial least square regression (Walkey et al., 2014, Brandmaier et al., 2012 and Wold et al., 2004), Neural Networks (Zarei et al., 2010), support vector machines (Fourches et al., 2010 and Liu et al., 2013), ensemble learning (Sellers et al., 2015 and Singh and Gupta, 2014) and genetic algorithms (Gajewicz et al., 2015) have been found useful for the establishment of the relationships between the molecular structures and biological activities of ENMs.

Computational models are evaluated based on their predictive accuracy (i.e. R2 for regression models and balanced class accuracy for classification models) derived from several common validation methods. For the development and the validation of QSAR models the scientific community has adopted the “OECD Principles for the Validation, for Regulatory Purposes, of (Q)SAR Models” (OECD, 2007). There are five principles that need to be taken into account:

- Defined endpoint,

- An unambiguous algorithm

- A defined domain of applicability,

- Appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness and predictivity for NM models, and

- Mechanistic interpretation, if possible.

In a recent publication (Puzyn et al., 2018), written by scientists involved in five recently completed European nanosafety modelling research projects, the application of the OECD validation principles in nano-QSAR modelling was critically reviewed. A main conclusion was that the OECD principles create an appropriate framework for validating nano-QSAR models, but there are issues that need particular attention. Among them, particular attention is drawn to the need for transparency and reproducibility of nano-QSAR models, documentation through the standard QMRF (QSAR Model Reporting Format) format and model representations using the Predictive Model Markup Language (PMML).

Integrating nano-QSAR models into the nanoinformatics infrastructure

First predictive nano-QSAR models integrated into NanoCommons KnowledgeBase Services that have been developed and are available through the NanoCommons infrastructure for generating and validating nano-specific quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (nano-QSAR) models and applying the models for predicting nanomaterial (NM) end-points for new materials that have not been tested experimentally.

Development of nano-QSAR model through the Jaqpot modelling platform

Jaqpot is a computational platform for in-silico modelling of chemical compounds, which has been developed by NTUA and is continuously being extended, so that it is updated with new developments and advances.

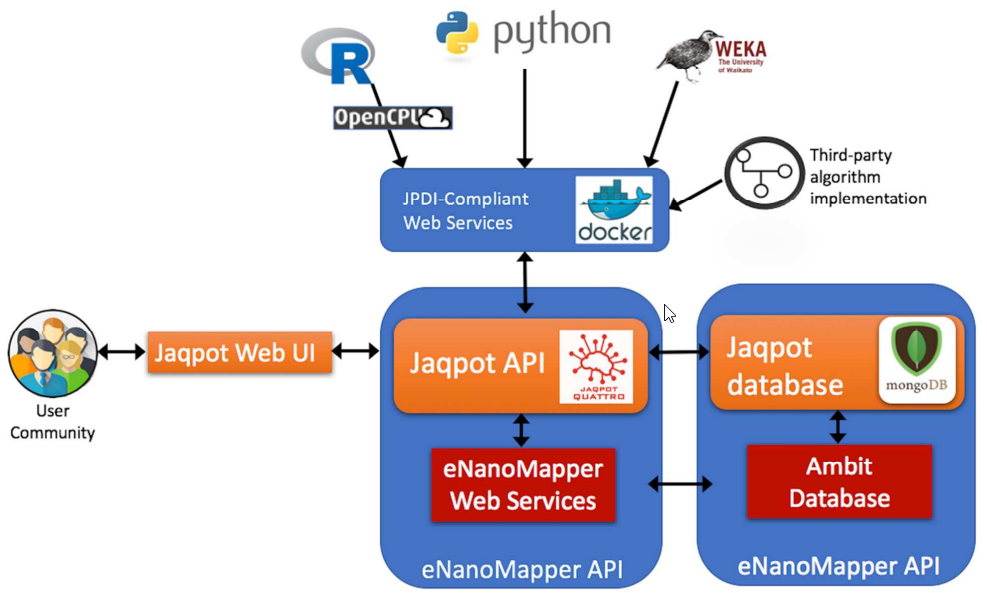

Figure 1. Schematic overview of JQ architecture (extracted from “Jaqpot Quattro: A Novel Computational Web Platform for Modeling and Analysis in Nanoinformatics, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.7b00223)

Jaqpot follows the microservice architecture where individual services are interconnected and linked together and with external services through REST API calls. The Jaqpot API constitute a means to develop user-friendly applications such as Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs), and Jupyter notebooks that consume Jaqpot services over the API, without the user having to deal with the technical burden of this implementation. The platform can be used to easily integrate QSAR and other types of models developed by any nanosafety community member into a single integrated platform, thus allowing users to select the optimal model for their needs, and facilitating benchmarking of models and integration of different approaches. A series of tutorials and instructional videos can guide potential users through the various functionalities of the Jaqpot platform, like developing, documenting, validating and sharing QSAR models:

Jaqpot Suite by Philip Doganis, NTUA (part of Jaqpot Hackathon)

Read-across predictions of nanoparticle hazard endpoints: a mathematical optimization approach

Jaqpot 5 Tutorial : How to access and use an existing predictive model

Jaqpot 5 Tutorial : User accounts

Jaqpot 5 Tutorial: How to manage and use organisations

Jaqpot 5 Tutorial: How to deploy a predictive model using the jaqpotpy library

Enalos cloud platform

Enalos Cloud Platform Transnational Access Services Through NanoCommons H2020 Infrastructure Project

Enalos Nanoinformatics Cloud Platform: A Safe-by-Design Tool for Functionalized Nanomaterials Tutorial

Nanoinformatics Model for Zeta Potential Prediction Powered by Enalos Cloud Platform Tutorial

References

- Brandmaier et al., 2012: Brandmaier, S.; Sahlin, U.; Tetko, I.V.; Öberg, T. PLS-optimal: a stepwise D-optimal design based on latent variables. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2012, 52(4), 975–983. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci3000198

- Cassotti et al., 2014: Cassotti, M.; Ballabio, D.; Consonni, V.; Mauri, A.; Tetko, I. V.; Todeschini, R. Prediction of acute aquatic toxicity toward Daphnia magna by using the GA-kNN method. Alternatives to Laboratory Animals: ATLA 2014, 42(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/026119291404200106

- Fourches et al., 2010: Fourches, D.; Pu, D.; Tassa, C.; Weissleder, R.; Shaw, S.Y.; Mumper, R.J.; Tropsha, A. Quantitative nanostructure-activity relationship modeling. ACS Nano 2010, 4(10), 5703–5712. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn1013484

- Gajewicz et al., 2015: Gajewicz, A.; Schaeublin, N.; Rasulev, B.; Hussain, S.; Leszczynska, D.; Puzyn, T.; Leszczynski, J. Towards understanding mechanisms governing cytotoxicity of metal oxides nanoparticles: Hints from nano-QSAR studies. Nanotoxicology 2015, 9(3), 313–325. https://doi.org/10.3109/17435390.2014.930195

- Hansen et al., 2013: Hansen, S.F.; Jensen, K.A.; Baun, A. NanoRiskCat: a conceptual tool for categorization and communication of exposure potentials and hazards of nanomaterials in consumer products. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2013, 16(1), 2195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-013-2195-z

- Liu et al., 2013: Liu, R.; Rallo, R.; Weissleder, R.; Tassa, C.; Shaw, S.; Cohen, Y. Nano-SAR development for bioactivity of nanoparticles with considerations of decision boundaries. Small (Weinheim an Der Bergstrasse, Germany) 2013, 9(9–10), 1842–1852. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201201903

- OECD, 2007: OECD Guidance Document on the Validation of (Quantitative) Structure-Activity Relationship ((Q)SAR) Models. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/env/guidance-document-on-the-validation-of-quantitative-structure-activity-relationship-q-sar-models-9789264085442-en.htm (Accessed: 31/05/19)

- Oh et al., 2016: Oh, E.; Liu, R.; Nel, A.; Gemill, K.B.; Bilal, M.; Cohen, Y.; Medintz, I. L. Meta-analysis of cellular toxicity for cadmium-containing quantum dots. Nature Nanotechnology 2016, 11(5), 479–486. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2015.338

- Pan et al., 2016: Pan, Y.; Li, T.; Cheng, J.; Telesca, D.; Zink, J.I.; Jiang, J. Nano-QSAR modeling for predicting the cytotoxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles using novel descriptors. RSC Advances 2016, 6(31), 25766– 25775. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA01298A

- Pandharipande et al., 2009: Pandharipande, P. V.; Mora, J.T.; Uppot, R.N.; Goehler, A.; Braschi, M.; Halpern, E.F.; … Harisinghani, M. G. Lymphotropic nanoparticle-enhanced MRI for independent prediction of lymph node malignancy: a logistic regression model. American Journal of Roentgenology 2009, 193(3), W230-237. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.08.2175

- Puzyn, et al., 2011: Puzyn, T.; Rasulev, B.; Gajewicz, A.; Hu, X.; Dasari, T. P.; Michalkova, A.; … Leszczynski, J. Using nano-QSAR to predict the cytotoxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles. Nature Nanotechnology 2011, 6(3), 175–178. (https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2011.10

- Puzyn et al., 2018: Puzyn, T.; Jeliazkova, N.; Sarimveis, H.; Robinson, R.L.M.; Lobaskin, V.; Rallo, R.; … Cronin, M.T. Perspectives from the NanoSafety Modelling Cluster on the validation criteria for (Q) SAR models used in nanotechnology. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2018, 112, 478-494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2017.09.037

- Sellers et al., 2015: Sellers, K.; Deleebeeck, N.; Messiaen, M.; Jackson, M.; Bleeker, E.A.J.; Sijm, D., van Broekhuizen, F.A. Grouping Nanomaterials - A strategy towards grouping and read-across. https://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/2015-0061.html

- Singh and Gupta, 2014: Singh, K.P.; Gupta, S. Nano-QSAR modeling for predicting biological activity of diverse nanomaterials. RSC Advances 2014, 4(26), 13215–13230. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RA01274G

- Walkey et al., 2014: Walkey, C.D.; Olsen, J.B.; Song, F.; Liu, R.; Guo, H.; Olsen, D.W.H.; … Chan, W.C.W. Protein Corona Fingerprinting Predicts the Cellular Interaction of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2014, 8(3), 2439–2455. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn406018q

- Wold et al., 2004: Wold, S.; Josefson, M.; Gottfries, J.; Linusson, A. The utility of multivariate design in PLS modeling. Journal of Chemometrics 2004, 18(3–4), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/cem.861

- Zarei et al., 2010: Zarei, M.; Khataee, A.R.; Ordikhani-Seyedlar, R.; Fathinia, M. Photoelectro-Fenton combined with photocatalytic process for degradation of an azo dye using supported TiO2 nanoparticles and carbon nanotube cathode: Neural network modeling. Electrochimica Acta 2010, 55(24), 7259–7265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2010.07.050