Corona modelling approaches and tools

Interactions of a foreign nanomaterial (NM) with biological tissues control its fate and biological activity, including cellular attachment, uptake and any eventual hazard. Quantitative study of these interactions is extremely challenging due to the presence of multiple molecule types and material chemistries - as well as structure-specific effects, and while the immense system size prohibits the atomistic level modelling. It is now well accepted that the interaction of NMs with biological fluids leads to the formation of a protein layer on the surface of the NM which is known as the protein corona. It has been established that the corona plays the central role in the bioactivity of the NM.

Interactions of a foreign nanomaterial (NM) with biological tissues control its fate and biological activity, including cellular attachment, uptake and any eventual hazard. Quantitative study of these interactions is extremely challenging due to the presence of multiple molecule types and material chemistries - as well as structure-specific effects, and while the immense system size prohibits the atomistic level modelling. It is now well accepted that the interaction of NMs with biological fluids leads to the formation of a protein layer on the surface of the NM which is known as the protein corona. It has been established that the corona plays the central role in the bioactivity of the NM.

Computer simulations of the interactions of NMs with proteins can offer a great support to experiments because of their great speed and flexibility (An et al., 2015). However, it has also been extremely challenging to develop a model that can predict the composition of the protein corona around an inorganic NM, as this depends on a multitude of physicochemical properties both of the protein, such as charge, isoelectric point and hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity and of the NM, such as size, shape, pH, hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity, and charge distribution. Still, successful approaches are emerging, which can be classified as physics-based or data-driven.

Physics-based modelling

Full-atomistic simulations have already proven to be a valuable tool in elucidating the binding mechanisms of proteins on metallic NMs (Brancolini et al., 2012; Ding et al., 2013; Khan et al., 2013). However, their performance is severely hindered by the inefficiency in simulating systems with large NMs due to the high number of pair interactions that need to be evaluated. To speed-up the calculations, a cut-off of at the order of a nanometer is often introduced. However, this results in an underestimation of the adsorption energies of proteins on NMs due to the neglect of the influence from the core of the NM, which contributes much to their mutual attraction (especially at radii of over 10 nm) and so cannot be neglected. A coarse grained (CG) model of protein-NM interactions can overcome most of the challenges in the inclusion of NM core in the interaction.

While the number of atom-atom pairs in this problem is extremely large, the overall energy includes numerous instances of the same contributions, like the pair interaction of a given amino acid (AA) with a unit volume of the NM. One can dramatically reduce the amount of calculations by pre-computing those interactions for the specific materials in a specific medium. For a protein, one would need to pre-compute the interaction potentials between the AA and the NM through water, bearing in mind that different potentials will be needed for the interaction with the NM surface and the core. Assuming that these interactions do not depend on the position of the AA inside the protein and are additive (the two most significant approximations of the model), one can quickly scan multiple proteins once the potentials are known.

A description of the systematic procedure of evaluation of the required potentials of mean force is out of scope for this Handbook. Instead, we refer to the summary provided in:

First corona simulation tools integrated into NanoCommons KnowledgeBase

This gives information on:

- Multiscale model of NM-protein interaction

- Coarse-grain protein model

- Coarse-grain NM

- Generation of surface potentials

- Generation of the core potential

- Evaluation of the adsorption free energy

- Simulation parameters as well as the software used (UnitedAtom, Power et al., 2019) and an example of using the tool within the NanoCommons KB for evaluation of adsorption energy of human serum albumin (HSA) protein onto gold NM .

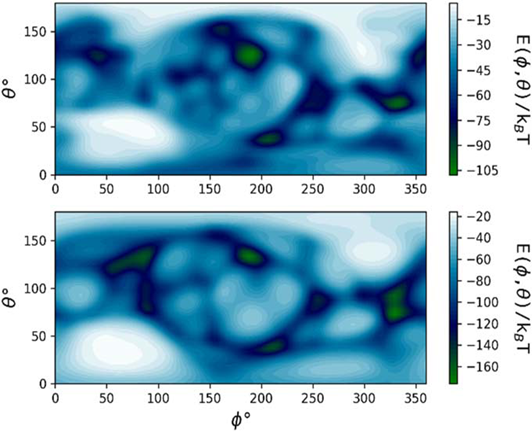

Orientation-specific binding energy E of HSA on an R = 5 nm (top) and R = 50 nm (bottom) Au NM calculated using the UnitedAtom software (Power et al., 2019).

Orientation-specific binding energy E of HSA on an R = 5 nm (top) and R = 50 nm (bottom) Au NM calculated using the UnitedAtom software (Power et al., 2019).

Additional training and an integrated approach using predictions and experimental data is available here:

Introduction to biocorona in silico modelling around nanoparticles

NanoXtract corona prediction model

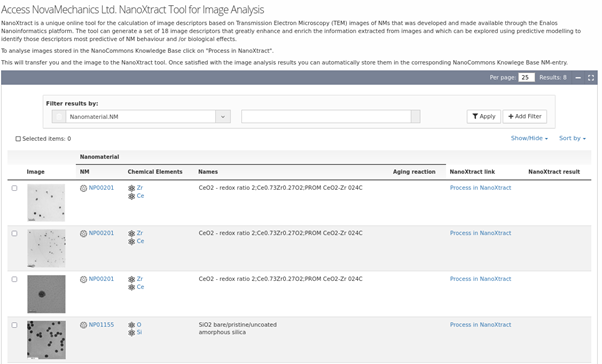

An integrated workflow based on the NanoXtract image analysis system enables experimental groups to upload NM images, extract multiple physical properties (size, diameter, roundness etc.) by image processing and feed this information into the physics-based binding energy prediction model (Power et al., 2019) to derive predictions about the absorption of specific proteins and to compare these with experimental data. Further post-processing is required to convert binding energies to a corona prediction to account for the specific concentrations of proteins, NM and protein geometry etc, (see Hasenkopf et al., 2022), with this tool providing a first screening to determine whether a protein is likely to feature in the corona and if so in which binding orientation.

NanoXtract Image analysis tool integrated into the NanoCommons KB, enabling upload of TEM images of NMs and automated extraction of a range of NM image descriptors.

NanoXtract Image analysis tool integrated into the NanoCommons KB, enabling upload of TEM images of NMs and automated extraction of a range of NM image descriptors.

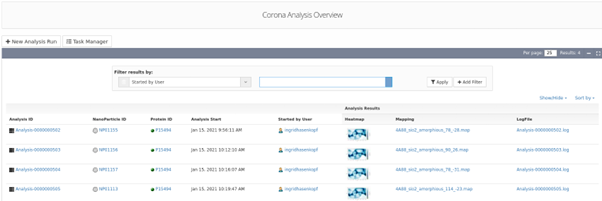

Binding energy analysis results list indicating the NM ID, the specific protein ID and the protein binding heatmap generated using UnitedAtom and the related outputs.

Binding energy analysis results list indicating the NM ID, the specific protein ID and the protein binding heatmap generated using UnitedAtom and the related outputs.

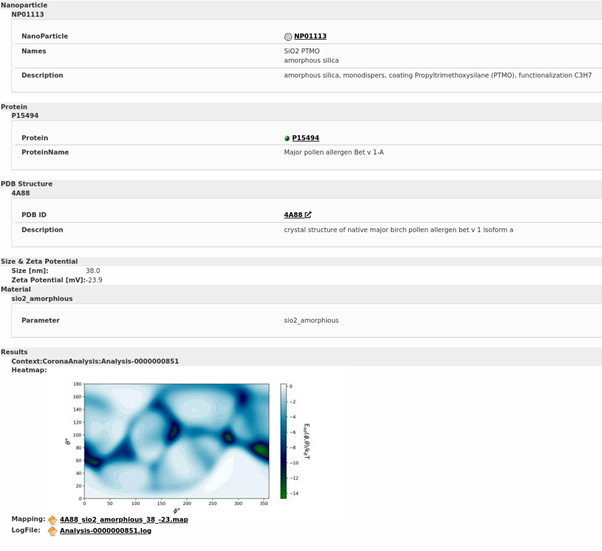

Results of binding energy prediction for one specific NM (Amorphous SiO2 NMs with a particular coating and surface functionalisation) interacting with one specific protein (major pollen allergen Bet v 1A in this case), indicating the heatmap and providing links to the mapping and logfile.

Results of binding energy prediction for one specific NM (Amorphous SiO2 NMs with a particular coating and surface functionalisation) interacting with one specific protein (major pollen allergen Bet v 1A in this case), indicating the heatmap and providing links to the mapping and logfile.

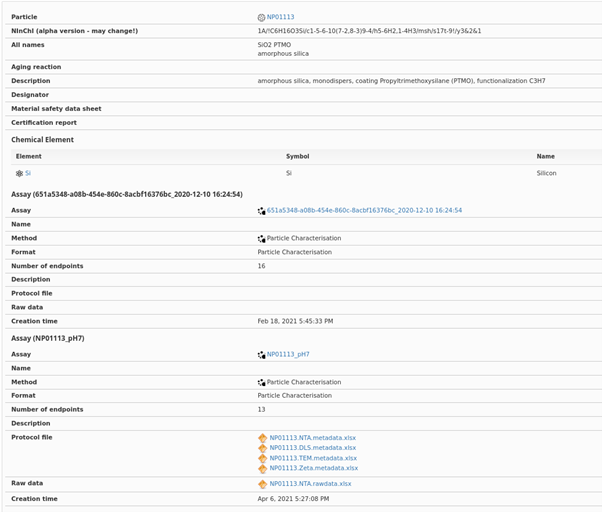

Detailed experimental results and metadata, as recorded in the NanoCommons KB. Note also that the links to the relevant experimental data are also provided, and to the ontology terms for the specific assays, the standard operating procedure or protocol. Additionally, the Nano-specific extension of the InChI (the so-called NInChI) as developed within NanoCommons (see Lynch et al., 2020) is also provided for the specific NM, noting that this may change as it is based on the prototype (alpha) version and is not yet an IUPAC standard.

Detailed experimental results and metadata, as recorded in the NanoCommons KB. Note also that the links to the relevant experimental data are also provided, and to the ontology terms for the specific assays, the standard operating procedure or protocol. Additionally, the Nano-specific extension of the InChI (the so-called NInChI) as developed within NanoCommons (see Lynch et al., 2020) is also provided for the specific NM, noting that this may change as it is based on the prototype (alpha) version and is not yet an IUPAC standard.

References

- An et al., 2015: An, D.; Su, J.; Li, C.; Li, J. Computational studies on the interactions of nanomaterials with proteins and their impact. Chin. Phys. B 2015, 24, 120504. https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1056/24/12/120504.

- Brancolini et al., 2012: Brancolini, G.; Kokh, D.B.; Calzolai, L.; Wade, R.; Corni, S. Docking of ubiquitin to gold nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 9863–78. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn303444b.

- Ding et al., 2013: Ding, F.; Radic, S.; Chen, R.; Chen, P.; Geitner, N.; Brown, J.; Ke, P. Direct observation of a single nanoparticle–ubiquitin corona formation. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 9162–9. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3NR02147E.

- Hasenkopf et al., 2022: Hasenkopf, I.; Mills-Goodlet, R.; Johnson, L.; Rouse, I.; Geppert, M.; Duschl, A.; Maier, D.; Lobaskin, V.; Lynch, I.; Himly, M. Computational prediction and experimental analysis of the nanoparticle-protein corona: Showcasing an in vitro-in silico workflow providing FAIR data NanoToday 2022, 46, 101561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nantod.2022.101561.

- Khan et al., 2013: Khan, S.; Gupta, A.; Nandi, C. Controlling the fate of protein corona by tuning surface properties of nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 3747–52.https://doi.org/10.1021/jz401874u.

- Power et al., 2019: Power, D.; Rouse, I.; Poggio, S.; Brandt, E.; Lopez, H.; Lyubartsev, A.; Lobaskin, V. A multiscale model of protein adsorption on a nanoparticle surface. Modelling Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 27, 084003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-651X/ab3b6e.