Flexibility vs. guidance

Establishing a system of clear guidance for metadata curation is, as shown already above, essential to enforce the use of standards and improve the completeness of reported data. Templates in the form of e.g., Excel files are a first step and preferable since most data providers are familiar with their usage. However, they have clear disadvantages summarised here:

- The use of standard templates is not part of the normal experimental workflow. Instead, customised templates are often used, almost doubling the time needed for data collection (once in the customised form and once in the standard format) even if no additional metadata is requested for improving quality and completeness.

- Even if spreadsheet software offers full flexibility with respect to the format, in which the data is structured, changes in the format often lead to incompatibility or even falsification of derived results.

- Even if spreadsheets were originally designed for tabular data, very complex structures are nowadays implemented in them, links between different cells and equations calculating derived results based on data in specific cells. Small sometimes unintentional changes, i.e., replacing an equation by its result, can break the complete spreadsheet but are very hard to identify.

- Integrating additional metadata often requires an adaptation of the automatic processing of the files, needed for the upload of the data into data warehouses. This is only possible for large amounts of data coming in this new format e.g., from a follow-up project reusing the template from its predecessor but not for individual dataset representing e.g., improvements of a specific method as done in ACEnano.

- Comparing spreadsheets is very complex and, thus, it is almost impossible to, e.g., automatically translate an earlier version of a template into an updated one. This is even true for different versions of the same dataset.

- One major advantage of spreadsheets is that graphs can be directly produced from the data but also that additional information like images to support the data can be integrated. However, even if it is possible to extract such graphs to include them in the data upload, identifying their purpose is impossible so that they cannot be annotated and indexed in the data warehouse.

- On-the-fly validation of the collected data within the spreadsheet software requires huge development efforts. Additionally, these efforts often have to be very specific to one template or even specific methods or assays reported in these templates. However, such validation and curation is absolutely essential to produce harmonised and interoperable data, which can then be successfully indexed in data warehouses. We are here only partly talking about scientific validation, in which the data is evaluated with respect to its plausibility to identify outliers or even errors in the experiment. It is starting with the much simpler technical validation. Renaming, even if it seems minor to a human being, of column names, spelling errors and even the case insensitivity or additional white spaces can break downstream processing of the files, which can only be recovered by human curation or implementing specific correction procedures.

- Even if data can be uploaded to many standard nanosafety or more general toxicology databases and data warehouses can be uploaded via web interfaces, the large majority of datasets are uploaded in the form of spreadsheets. As already expressed in point 3, validation of the files regarding the structure of the reported data has to be performed to guarantee consistency in the data warehouse. Such processing steps sometimes also require semantic annotation with ontologies and the mapping to a semantic model implemented in the data warehouse. If one of these steps fails because of errors in the files, the data uploader, which is sometimes not the same person as the data provider, needs to go back into the file to find and remove the errors often with the help of the data provider. This is a slow and time-consuming procedure.

To get beyond spreadsheets, better tools need to be developed, which allow integrating the early stages of data management directly into the normal experimental workflows. Similar to electronic lab notebooks (ELNs), which support the user to document their study designs and performed experiments in a more standardised form allowing for easy reuse, sharing but perhaps even more important already in a digitalised form to be directly integrated into reports and publications. Data management is not a strength of the existing ELNs and additional tools should be created, which give the user a natural way to collect their data directly during the experiment as electronic records. This would bring the benefits that quality controls like completeness of metadata, formal correctness and compliance to standards as well as support for ontology annotation can be directly integrated. Such tools could be even combined with ELNs to give the user one easy-to-use interface for all documentation tasks. Such tools would be clearly targeting the goal to prepare the data for upload to databases (internal) and data warehouses (public) but could be designed more independent of those and in principle just result in a spreadsheet, which the user could take as a starting point for further analysis.

The ACEnano approach is clearly not the complete solution addressing all these issues. However, it showed how modern web technology can guide the user during the collection and upload of metadata on the specific use case of the ACEnano data warehouse. The focus was on the balance between defined standards of absolutely essential metadata and flexibility to allow for adaptation of and additions to the collected metadata e.g., to cover specificities of different lab equipment. In the following, we will present some examples of how the web forms were designed to implement parts of the protocols and data workflow questionnaires.

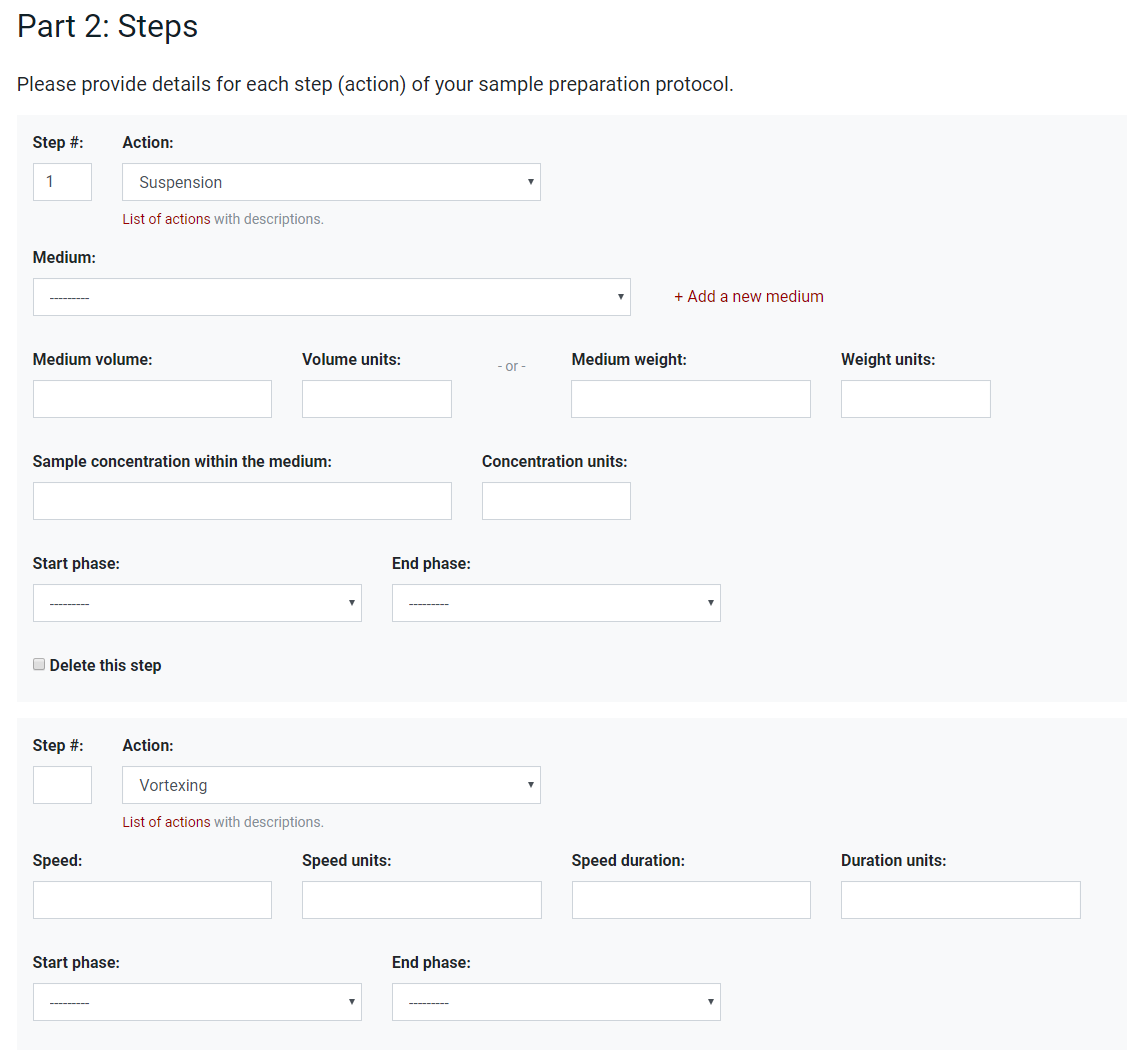

The first example in Figure 1 shows the metadata needed to describe different steps (actions) used in sample preparation. This is a relatively rigid interface and could probably also be implemented in a spreadsheet. However, the predefined actions, as well as other parameters like solvents, remove the possibility of including spelling errors and can internally be associated with the ontology entries. Additionally, essential and optional fields can be treated separately with the first needed to be filled in before the user can progress to the next step. Additional flexibility is given by allowing the user to define customised solvents in another interface (not shown in the figure).

Figure 1. Interface for metadata describing different actions as part of the sample preparation protocol

Figure 1. Interface for metadata describing different actions as part of the sample preparation protocol

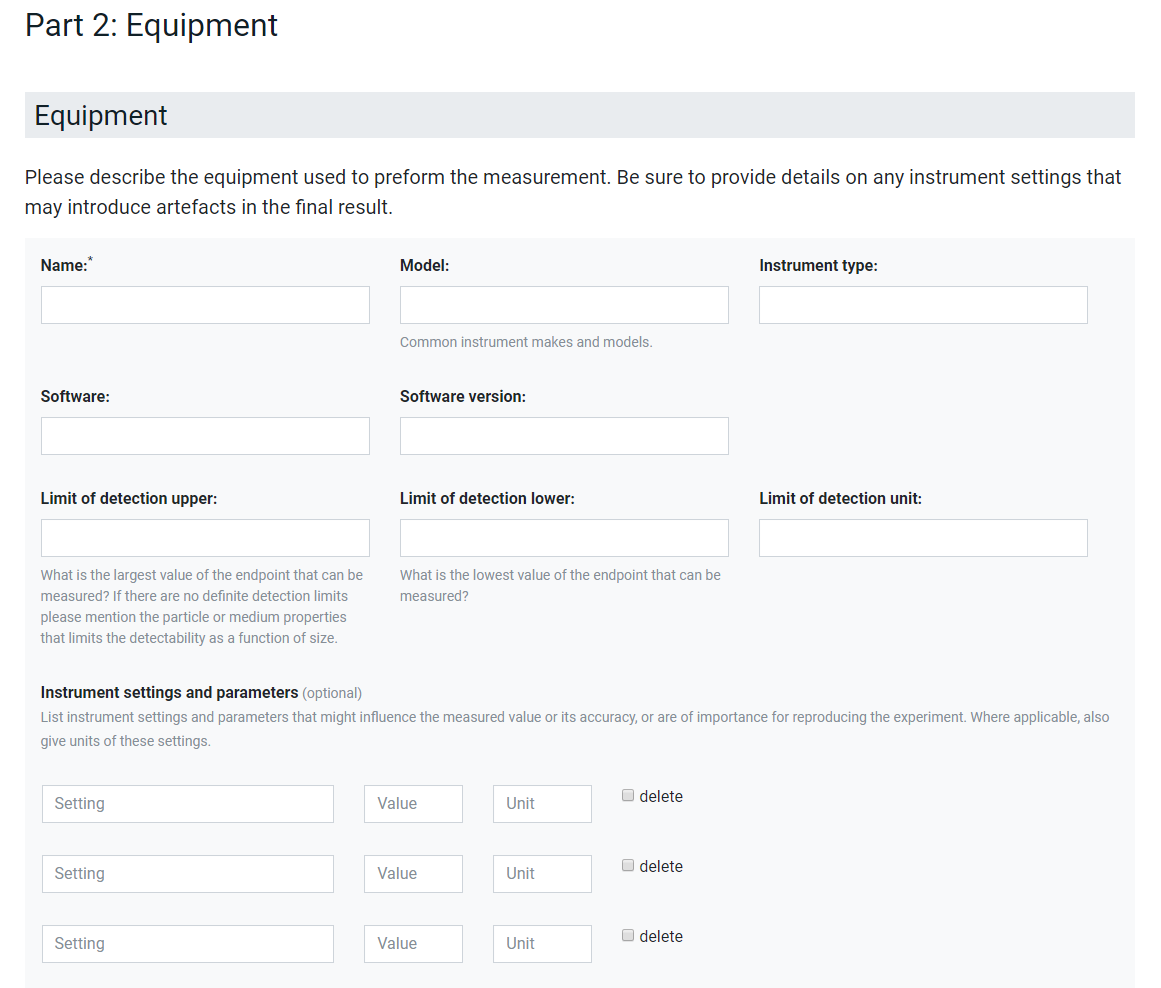

In the second example of Figure 2 the documentation of lab equipment is presented. Here, a small number of standard fields like the name, model, software and detection limits are predefined. Specific instrument settings and parameters can then be included. At the moment, which parameters are reported is completely decided by the user but the predefined structure of the interface provides the data already in a machine-readable way and the integration of an ontology lookup service [] as shown in Figure 3 harmonises the used terminology, gives semantic meaning to the metadata and reduced errors like spelling mistakes. In this way, data can be combined even if the users decide on a different ordering of the parameters. Additionally, the possibility to reuse existing protocols helps users to agree on metadata to be reported as minimal reporting standard in an interactive process especially for methods where such do not exist yet. However, more guidance should be given in the future e.g., by providing lists of standard metadata for specific methods, assays and equipment. Finally, it should be noted that ACEnano encourages to also report on equipment often seen as less relevant like plates, pipettors, pipettes and tips but which have been shown to sometimes cause artefacts in the data. However, this cannot be enforced by the interface and has to be agreed on in best-practice guidelines.

Figure 2. Interface for metadata describing experimental equipment and specific instrument settings and parameters

Figure 2. Interface for metadata describing experimental equipment and specific instrument settings and parameters

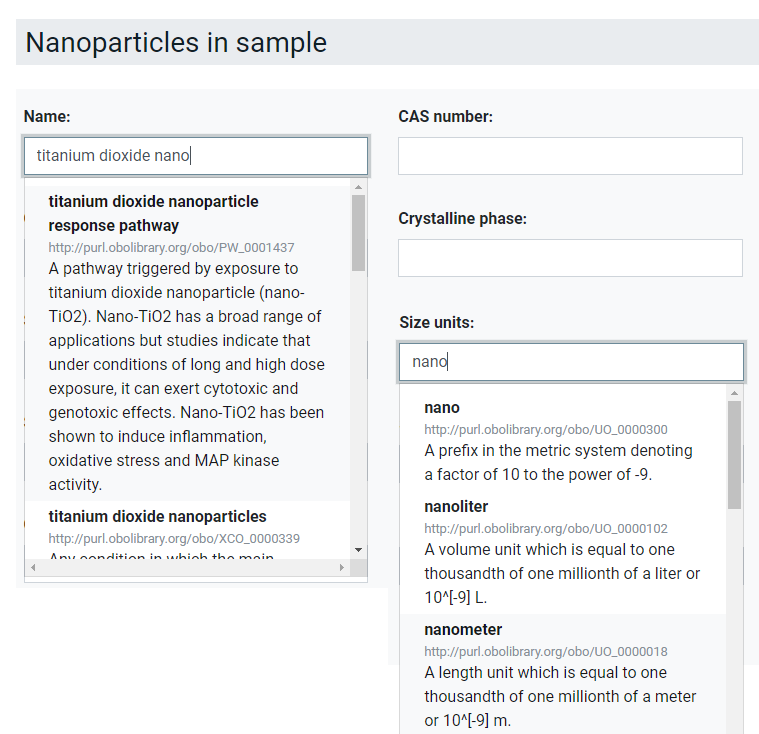

Figure 3. Ontology lookup service implemented in ACEnano to guide the data provider towards the use of harmonised and standard terminology

Figure 3. Ontology lookup service implemented in ACEnano to guide the data provider towards the use of harmonised and standard terminology

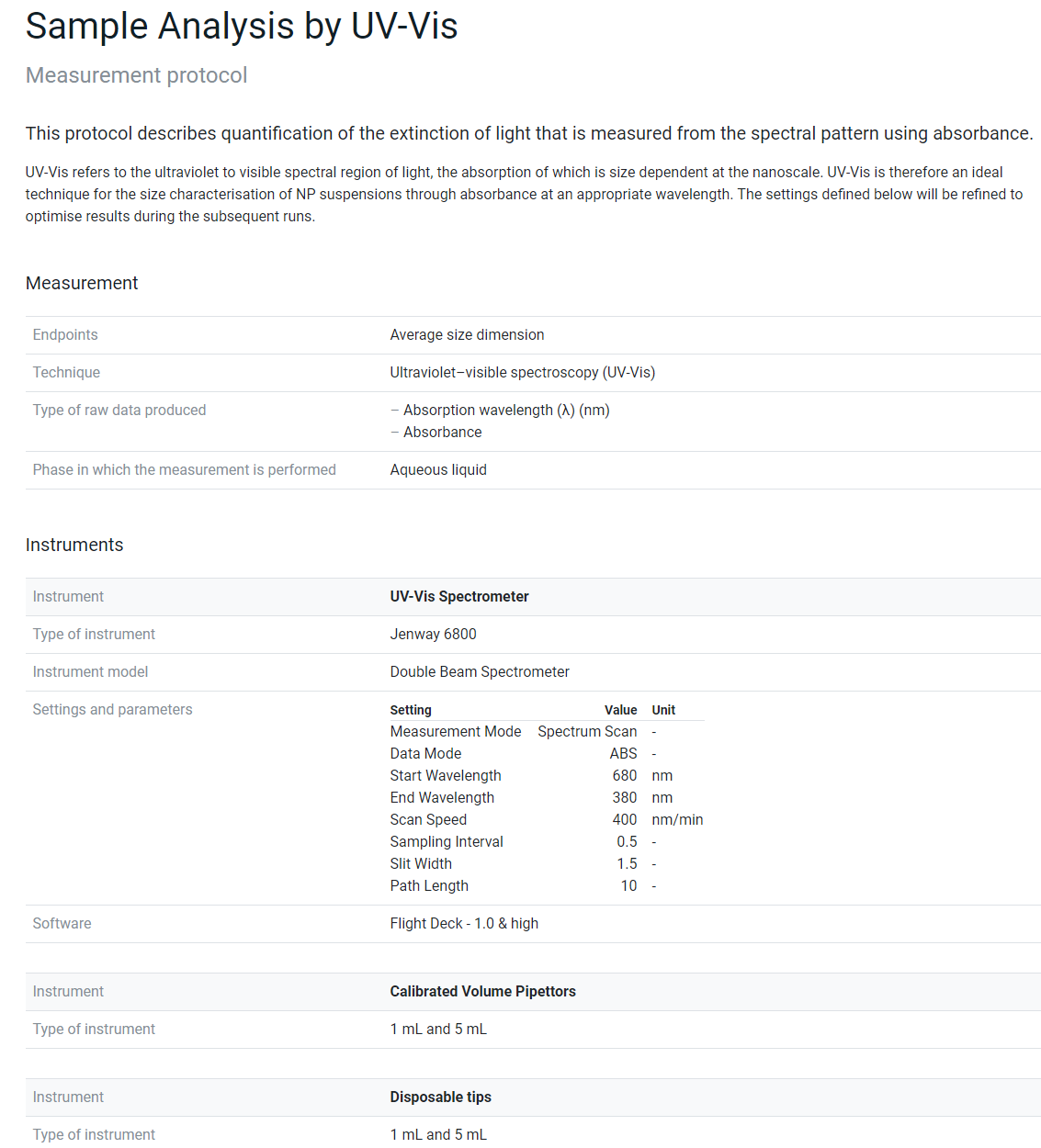

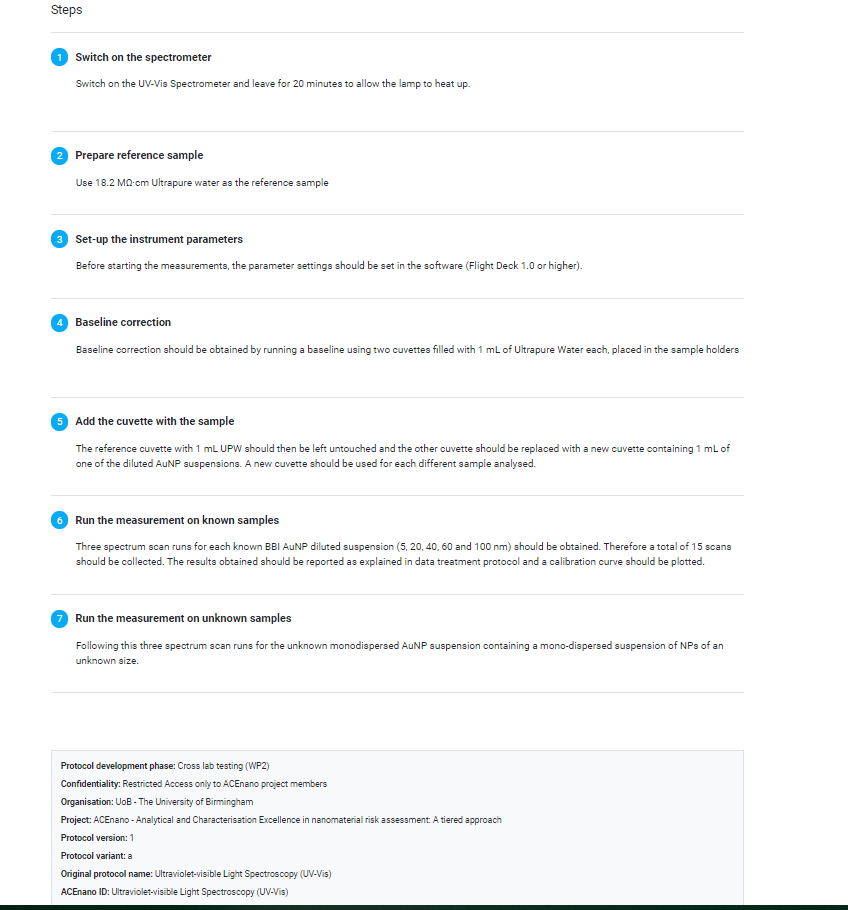

Figure 4 shows the results of reporting a measuring protocol for sample analysis by UV-Vis. The first part is the structured metadata on the endpoint, technique and equipment including the predefined fields and the user-provided specific instrument settings and parameters. The second part is a human-readable step-by-step instruction of how the experiment was performed, which is stored as metadata in addition to the structured metadata of part 1 and demonstrates one area, where the combination of ELNs and data management tools could be very beneficial by using the tooling of the ELNs to document the steps and to provide them to the protocols and data management solution to be able to store them with the data.

Figure 4. Metadata provided for a measurement protocol analysing a NM sample with UV-Vis

Figure 4. Metadata provided for a measurement protocol analysing a NM sample with UV-Vis

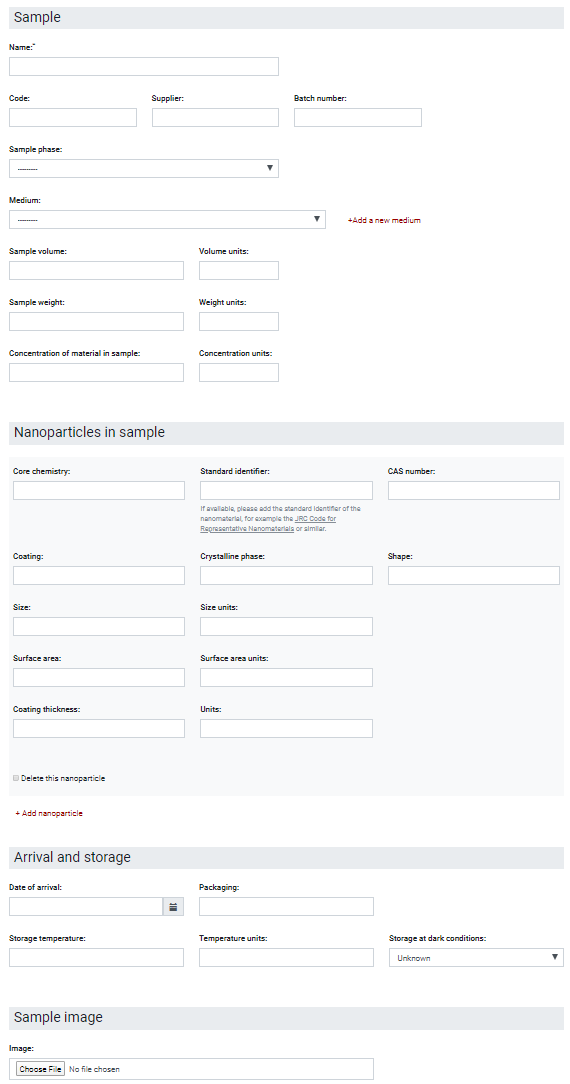

An important part of the data workflow is to provide information on the sample (see Figure 5), which will be used here as the last example of the ACEnano metadata capturing approach and relate it to the NanoFASE approach described before. The sample is described in detail using different parameters (names and other identifiers, the sample physicochemical characteristics like its phase, vehicle, volume, weight, concentration, etc). The nanomaterials that are contained in the sample are also described separately using different identifiers and physicochemical parameters. In addition, information regarding the storage conditions as well as a representative image of the sample can be added to the workflow. At the moment, this webform is quite rigid with the only flexible part consisting of the possibility to specify multiple nanoparticles to allow for covering of mixtures. However, as presented in the description of the NanoFASE concept, the NM might have already undergone multiple transformation due to environmental or human exposure and this fate and lifecycle state has an immense influence on the NM characteristics and needs to be reported with the data. Therefore, the concept of instances needs to be included in the ACEnano metadata schema in the near future to go beyond the requirements of the ACEnano project and allowing the linking of physicochemical characterisation data with exposure, fate and finally hazard data stored in other databases for samples of the same lifecycle state of a NM. Additionally, new specifications to unambiguously identify an NM down to a specific nanoform or to group experiments based on the same starting material should be included based on the InChI for nano line notification (Lynch et al., 2020) and the European Registry for Materials (van Rijn et al., 2022), respectively.

Figure 5. Metadata used for the description of the sample analysed

Figure 5. Metadata used for the description of the sample analysed

References

- Lynch et al., 2020: Lynch, I.; Afantitis, A.; Exner, T.; Himly, M.; Lobaskin, V.; Doganis, P.; Maier, D.; Sanabria, N.; Papadiamantis, A. G.; Rybinska-Fryca, A.; Gromelski, M.; Puzyn, T.; Willighagen, E.; Johnston, B. D.; Gulumian, M.; Matzke, M.; Green Etxabe, A.; Bossa, N.; Serra, A.; Liampa, I.; Harper, S.; Tämm, K.; Jensen, A. C.; Kohonen, P.; Slater, L.; Tsoumanis, A.; Greco, D.; Winkler, D. A.; Sarimveis, H.; Melagraki, G. Can an InChI for Nano Address the Need for a Simplified Representation of Complex Nanomaterials across Experimental and Nanoinformatics Studies? Nanomaterials 2020, 10 (12), 2493. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10122493.

- van Rijn et al., 2022: van Rijn, J.; Afantitis, A.; Culha, M.; Dusinska, M.; Exner, T.E.; Jeliazkova, N.; Longhin, E.M.; Lynch, I.; Melagraki, G.; Nymark, P.; Papadiamantis, A.G.; Winkler, D.A.; Yilmaz, H.; Willighagen, E. European Registry of Materials: global, unique identifiers for (undisclosed) nanomaterials. J. Cheminform. 2022, 14, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-022-00614-7.

Keep on reading about (meta)data concepts

NANoREG templates covering OECD endpoints